A people-first approach to retrofit

We now have the opportunity and knowledge to help homeowners and building managers move away from the destructive paradigm of air temperature and fabric-first retrofit.

|

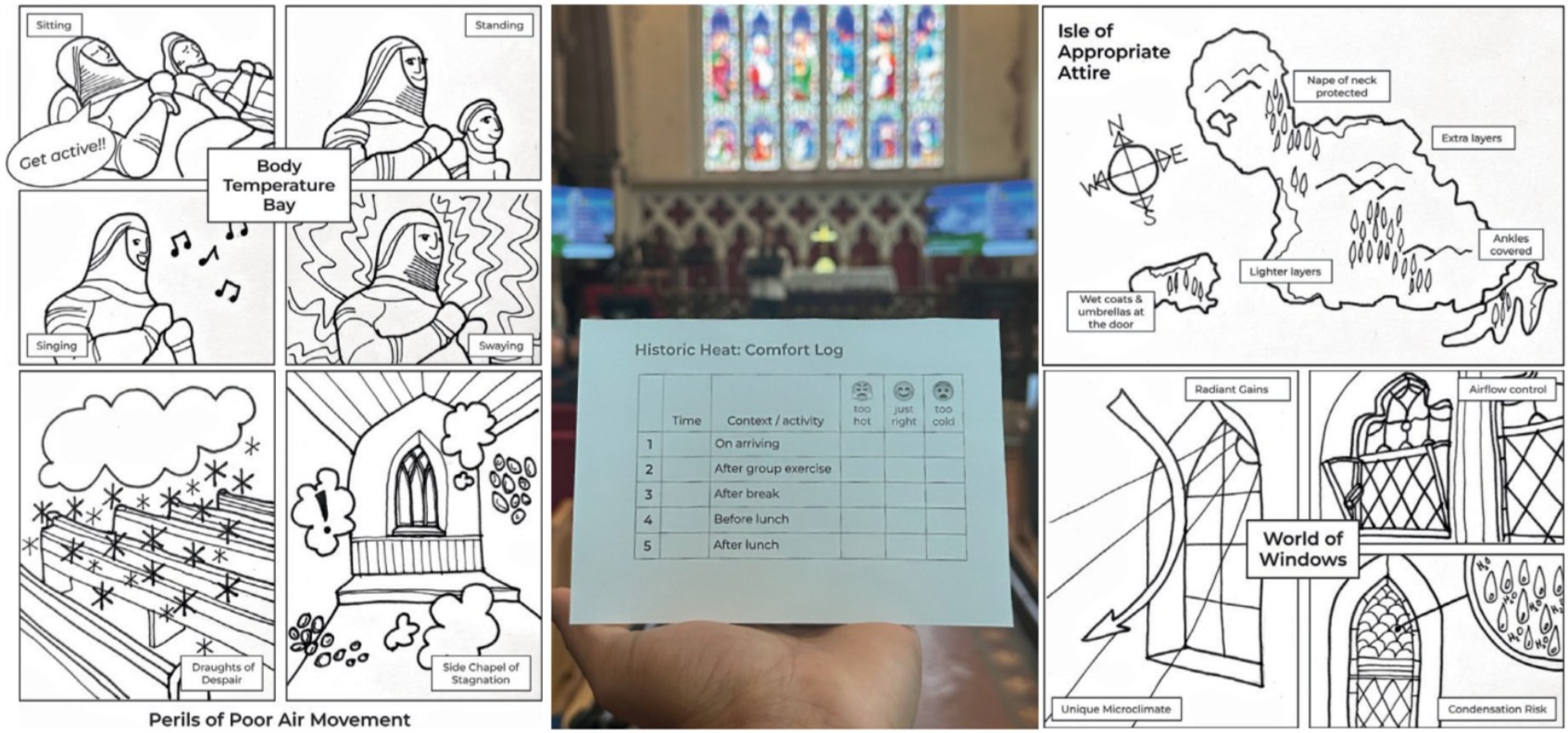

| Comfort varies from one person to another according to age, attire, level of activity, air-movement, humidity and many other factors, of which temperature is just one. (Photo: Cheribim Ltd). |

It is surprisingly easy to show that indoor air temperature is a poor guide to thermal comfort and one that encourages maladaptation.[1] Nonetheless, temperature is currently the unquestioned starting point of all Global North definitions of healthy and useable building environments.

The unfortunate outcomes of this paradigm have been many. To control air temperature sustainably, building envelopes must be sealed and heavily insulated. Alas, ‘fabric-first’ action of this type leads to problems with both comfort and indoor air quality, and to carbon-expensive failures of materials and structures. Since the industrial revolution, buildings have become markedly less healthy for their occupants,[2] a problem that has accelerated since the 1960s. As the climate warms, fabric-first retrofit risks causing dangerous overheating, especially in cities. Worse, despite the great quantities of fossil-fuel energy that have been devoted to it, ‘comfort’ has proved elusive. Over all this hangs the awful legacy of applying combustible insulated cladding to the outside of residential buildings, as highlighted by the Grenfell disaster.

Fortunately, the pre-carbon past and vernacular practice in the Global South provide us with many cheap and demonstrably effective tools for constructing and operating buildings in ways that are comfortable and healthy for all occupants and all uses, and which at the same time use little or no energy.[3] To this tried-and-tested toolbox from pre-carbon history we can now add some useful ‘post-carbon’ ideas: from familiar and effective older inventions such as vertically sliding sash windows and awnings, to modern innovations such as acrylic glazing, ceiling fans or safe ways to ‘heat the person, not the building’. If those tools that do require some operational energy can be powered from renewable sources, we immediately unleash enormous potential for rapid, effective and safe climate action, all at little cost in terms of either money or carbon.

Field research has already conclusively shown that many occupants of historic buildings do become adept at ‘sailing their buildings’, finding clever ways to make their homes or offices work for their particular needs.[4] Unfortunately in the Global North even the most thoughtful of these building managers lack some fundamental knowledge of buildings and comfort – knowledge that was once ubiquitous. For most professionals, the problem of ‘unknown unknowns’ is even more acute: almost nothing is currently taught of either history or first-principles science. Thus the category error around air temperature that underpins current approaches to operating and retrofitting buildings goes unrecognised, and unaddressed.[5]

It is imperative for us to start making this knowledge commonplace once again. How can this be done, especially given the current dominance of market-centred narratives around retrofit? What information is needed to support occupants and managers as they learn to ‘sail’ their buildings? Specifically, how do we give people the confidence to trust their own senses over a thermometer, and to confidently choose people-centred options for supporting the ways in which they wish to use their buildings?

Recent research is giving us clues. Our own project is proving particularly exciting: Historic Heat, a collaborative programme between Cheribim Ltd (founded by Katie Steele) and the Diocese of Sheffield, part funded by Innovate UK, which responds to the Church of England’s aim of transitioning to net zero operation by 2030. The aim is to trial a people-first approach to retrofitting, with a particular emphasis on maximising the use of the buildings. Early indications are that the approach we have been testing could serve as a model for other types of building under other types of use, so we thought it timely to provide a brief summary here.

The project team is working directly with diocesan support officers and more than 100 managers and volunteers in 85 churches. The 20-month project is bringing front-line volunteers together with experts, through:

- workshops, where the emphasis is on exploring the basic assumptions around comfort, and on co-creation: developing potential solutions for context-specific problems, inspired by history and the latest thermal physiology research

- easily accessible background support via site visits to every church, a series of information videos, and continuing one-to-one support for questions and ideas

- environmental monitoring using simple exterior and interior thermohygrometric parameters, and sharing the results on a real-time dashboard.

The Cheribim team make the initial sensor installation during a site visit to the church, in the course of which the building and the needs of its users are discussed in detail with the church managers. We have found that empathy is perhaps the key factor in gaining stakeholder engagement.

The monitoring helps the volunteers understand their building, and learn to recognise problems such as hidden water leaks that will affect the absolute humidity or how humidity responds to air-temperature changes. Since heating accounts for on average 80 per cent of a church’s energy demand,[6] it is clearly a central target for sustainability action. At the time of writing, some 67,500 hours of space heating have already been captured through the sensing data. The dashboard graphs confirm that heating the air is a complicated and unreliable approach to thermal comfort, as well as being expensive (especially for mass buildings with tall ceilings).

Some problems went unrecognised until revealed by the monitoring. For example, one churchwarden believed that their heating was responsive within about an hour, but the monitoring showed that for a 10 am service the system came on at 2 am (despite the temperature already reading 16 degrees centigrade), before reaching a peak of 20.5 degrees at 7 am, when the building was still empty.

Data can be collated to extract broader insights for support officers, energy auditors and conservation architects: for example, the proportion of churches with relative humidities above 80 per cent. Algorithms have been developed to estimate never-before-known information such as heating-use hours; and AI-enabled software is helping to analyse key factors in environmental performance (anything from the buildings overall condition to the wall materials in specific areas). This is helping the diocese to plan effective use of its own resources, for example distributing funding for energy audits.

The workshops have given the team the chance to work closely with a wide spectrum of stakeholders, all of whom showed themselves to be deeply engaged and ready to embrace a more sustainable approach to using their buildings. As invited experts, Robyn Pender and Bill Bordass [7] have been leading sessions and supporting the delivery of key-topic exercises around simple building physics and thermal physiology.

Each workshop takes place in a different church involved in the project, which supports the direct application of new learning within the surrounding environment (and crucially with those using and managing the building). Exercises adopt an active-learning approach, [8] promoting proactive, creative and reflective engagement. From role-playing being water molecules in the air to creating collages about comfort, there is ample opportunity to discuss and theorise, and have fun. Participants have shown a particular interest in the commonsense historic ‘hacks’ and ‘habits’ for improving comfort, for example the use of radiant breaks (wall hangings, curtains and clothing), or learning how to safely use their windows to control humidity.

A typical church’s children’s corner often already demonstrates an innate understanding of comfort: supplied with rugs, cushions and warm, coloured textiles, and thoughtfully adapted for its specific use. Hunting through the building for signs of historic tricks is an extremely popular exercise. In medieval churches, it is extraordinary how many features, such as hooks for wall draperies and supports for the rails of door curtains, do still survive, even in buildings that have been much altered.

Once they have been armed with basic information about the history and the science, the participants have shown extraordinary open-mindedness and creativity in approaching the problems of discomfort in their own buildings, recognising that the goal of creating one ‘ideal’ environment (into which must be fitted every user and every use) is fundamentally flawed. A ground-breaking insight from attendees is that this fact can usefully be turned on its head. By actively embracing the different thermal requirements of various users and uses, the building’s quirks become advantages to be exploited rather than problems to be solved.

To give one example: a workshop began discussing the fact that different areas of the building would always be warmer or colder. A creative participant suggested that the church could be mapped into zones for different thermal tastes or needs. The obvious example given was worshippers suffering from hot flushes, who often preferred to sit in draughts or by cool, uncovered stone walls. This idea caught the imagination of others in the workshop, and a quick-fire discussion produced the idea of correlating coloured seat cushions to comfort maps created in collaboration with the congregation. This would at the same time support the congregation developing its own understanding of the underlying principles. We are hoping to see this specific experiment taking place this winter.

Each church is encouraged to adapt their sensor layout to test their theories of how their building might be behaving, or to investigate their experiments in people-first retrofit. Monitoring confirms that people-centred tools will rarely produce any significant change in air temperature, even when comfort is greatly improved; the human body is by far the best comfort sensor. In this way, small-scale trials with wall draperies in two churches (one Grade I medieval, the other Grade II Victorian) have already provided evidence that these simple passive interventions provide immediate benefits; and as other research has shown, being able to react immediately and effectively to crises of discomfort is key.[9]

Another notable success of the project has been that most or all participants have expressed themselves keen to experiment not only in their own churches, but in their own homes. A frequent suggestion is that workshops could be held in churches for locals who are not part of the congregation, but who would be interested and enthusiastic about people-first retrofit.

This is demonstrating people-first retrofit at its best, so a key in the project’s final stages will be to find ways for the churches to share their experiences and experiments, and thus to learn from each other. It is probably no coincidence that, essentially, this is grass-roots research run on shoestrings by passionate researchers. On top of good science and history, and together with a healthy dose of empathy, passion driven by co-creation does seem to be essential to creating building users willing and able to turn away from the familiar, but unhelpful and energy-expensive.

To produce wider change at the speed needed, however, participants will need to be empowered to lead simple workshops on their own, spreading the messages more widely. Would this be risky, or is it perhaps too ambitious? History and current practice in the Global South suggest that it might actually be perfectly achievable. People-first retrofit can be seen and felt immediately, so good practice is quickly supported by lived experience.

Robyn and Bill’s ‘teach a man to fish’ approach to sharing their deep technical and applied expertise feels as innovative in the project’s context as making environmental monitoring sensors accessible to all churches everywhere. Equipped with the fundamental principles which underpin phenomena that impact - and give clues to - buildings’ thermal performance, anyone grappling with the day-to-day management and adaptation of historic buildings towards a sustainable status quo suddenly has the ability to make progress against their big-intervention decisions, without reliance on expert or specialist input.

Far from accelerating poorly-informed maladaptation, or threatening the business of conservation-services provision, the approach in fact safeguards and stimulates on both fronts. Knowledge of the fundamental principles of building physics and thermal physiology, combined with digital tools to share a single-source of truth amongst stakeholders, enable those on the ground to knit together discrete expert insights with their daily experience and activity, and make visible pertinent factors over time. Immediately they can recognise missteps and the manifestation of common issues or opportunities in the context of their unique circumstances. Consultants, by virtue of this, are freed to focus on more complex, specialist tasks, better-informed from the outset to maximise the return on investment of time and expertise.

Collectively, a step-change in the efficacy and economy of the sector can be created by such a shift, hiving off the relatively low-skilled information-gathering essential to getting clients up to speed, and eking out situation-specific factors. This project has cultivated many transformational learnings, but without doubt the most important and ground-breaking has been Robyn and Bill’s transformational modelling of the most strategic thing sector professionals at this critical, transitional time can do: support their client-base to become high-quality, high-value ‘informed clients’ – and reap the benefits. With the Grenfell report now published, there is a sense of change in the air. Those of us working in the historic built environment have the opportunity and the knowledge – and indeed the responsibility – to help homeowners and building managers to move away from the destructive paradigm of air temperature and its offspring, fabric-first retrofit, and to replace it with fast, effective and sustainable people-first action.

References

- [1] Pender, Robyn (2024) ‘Climate action: comfort is a crucial missing piece of the puzzle’, IHBC Yearbook.

- [2] Pallubinsky, H., Kramer, R.P., van Marken Lichtenbelt, W.D. (2023) ‘Establishing resilience in times of climate change: a perspective on humans and buildings’, Climate Change, Vol.176.

- [3] ‘Climate action: comfort is a crucial missing piece of the puzzle’ (ibid).

- [4] Wise, Freya, Moncaster, Alice, and Jones, Derek (2021) ‘Rethinking retrofit of residential heritage buildings’, Buildings and Cities, Vol. 2, No.1.

- [5] Pender, R. and Lemieux, D.J. (2020) ‘The road not taken: building physics, and returning to first principles in sustainable design’, Atmosphere 11.

- [6] www.churchofengland.org/resources/churchcare/advice-and-guidancechurch-buildings/heating

- [7] W Bordass & C Bemrose, Heating Your Church, 2nd Edition, Church House Publishing (1996)

- [8] Silberman, M (1996) Active Learning: 101 strategies to teach any subject, Allyn and Bacon, Massachusetts.

- [9] Zhang, H, Arens, E. and Pasut, W. (2011) ‘Air temperature thresholds for indoor comfort and perceived air quality’, Building Research and Information, Vol. 39, No.2.

This article originally appeared in the Institute of Historic Building Conservation’s (IHBC’s) Context 181, published in December 2024.

Robyn Pender, who has retired from Historic England, is involved in the Climate Heritage Network and Whethergauge, and at Cathedral Communications, where she is one of the editors of the Building Conservation Directory and Historic Churches.

Katie Steele is the founder and CEO of Cheribim, and a visiting tutor at Birmingham City University. Previous roles include historic churches support officer with the Diocese of Sheffield and listed buildings committee secretary for the Baptist Union.

Amy Graham, chief heritage officer of Cheribim, is a former local history officer for the Royal Borough of Kingston upon Thames.

--Institute of Historic Building Conservation

Related articles on Designing Buildings Conservation.

- Conservation.

- Energy Efficiency and Comfort of Historic Buildings.

- Energy efficiency of traditional buildings.

- Heritage.

- Historic environment.

- IHBC articles.

- Institute of Historic Building Conservation.

- New HES national centre for traditional building retrofit.

- Retrofit and traditional approaches to comfort.

- Retrofitting traditional buildings.

- Sustainable heating for listed buildings.

- The ability to retrofit is important in all areas of life.

IHBC NewsBlog

Latest IHBC Issue of Context features Roofing

Articles range from slate to pitched roofs, and carbon impact to solar generation to roofscapes.

Three reasons not to demolish Edinburgh’s Argyle House

Should 'Edinburgh's ugliest building' be saved?

IHBC’s 2025 Parliamentary Briefing...from Crafts in Crisis to Rubbish Retrofit

IHBC launches research-led ‘5 Commitments to Help Heritage Skills in Conservation’

How RDSAP 10.2 impacts EPC assessments in traditional buildings

Energy performance certificates (EPCs) tell us how energy efficient our buildings are, but the way these certificates are generated has changed.

700-year-old church tower suspended 45ft

The London church is part of a 'never seen before feat of engineering'.

The historic Old War Office (OWO) has undergone a remarkable transformation

The Grade II* listed neo-Baroque landmark in central London is an example of adaptive reuse in architecture, where heritage meets modern sophistication.

West Midlands Heritage Careers Fair 2025

Join the West Midlands Historic Buildings Trust on 13 October 2025, from 10.00am.

Former carpark and shopping centre to be transformed into new homes

Transformation to be a UK first.

Canada is losing its churches…

Can communities afford to let that happen?

131 derelict buildings recorded in Dublin city

It has increased 80% in the past four years.